Published By: Lamont Jack Pearley

Juneteenth should always be mentioned with the term “African American Traditional Music!” Juneteenth is the celebration of the releasing of the last remaining slaves after the emancipation proclamation and civil war. In 1865, June 19 Union soldiers led by Major General Gordon Granger shared the news that the war is over and the slaves were now free, in Galveston, Texas. Ironically, this freedom came after the actual date of 1863, when Lincoln made his declaration. Though, the first documented celebration of emancipation dates back to March 2, 1807, when Congress passed a bill to halt the importation of “slaves” into the United States, effective January 1, 1808, which prompted Absalom Jones, a pastor at St. Thomas’s African Episcopal Church in Philadelphia to call for a special commemoration of the ban. “Let January 1, the day of the abolition of the slave trade in our country, be set apart every year, as a day of public thanksgiving for that mercy,” he declared. The 1808 ban fueled annual public observances, primarily religious gatherings in northern cities such as New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, called Emancipation Day.

Though the initial celebration of January 1, 1808, was the first recording of Emancipation Day, June 19 then took on the name Emancipation Day, as well as Jubilee Day, now known as Juneteenth. In 1866, during the first celebration of “Jubilee Day” aka Juneteenth, newly freed African Americans sang Black Spirituals such as “Go Down Moses,” and “Many Thousands Gone.” In resemblance of Independent day, they released a barrage of fireworks.

The fact is, Texas was the last to free the slaves. There are many reasons for this notion. Some theories suggest the messenger of the news of freedom was killed before reaching Texas, and some say the information was intentionally withheld in hopes to continue the abuse and exploitation of free labor. Either way, the information seemed to have arrived two years late.

To understand why this would be the case in Texas, we must visit the history and origins of the state. African Americans were among the first who settled Texas in the 17th and 18th century. There were free and enslaved black and mixed-race people. Interracial marriage was legal and very common. The Spanish rule was not as heinous as the French or the British — the first white inhabitants derived from southern states and believed in the notion of blacks being slaves. Even though the independence of Mexico from Spain put a halt on slavery, the surge of white settlers resulted in the growth of slavery.

The Texas Constitution of 1836 gave protection to slaveholders while further controlling the lives of enslaved people through new slave codes. Furthermore, in 1836, there was 5,000 African Americans there were enslaved in Texas (13 percent of the population). By 1840, 13,000 African Americans were slaves in Texas. By 1850, 48,000 were enslaved, and by 1860, 169,000(30 percent of the Texas population). Rumors of a slave insurrection circulated in 1860, which led to Texas suspending civil liberties of Black people. Suspected abolitionists were made to leave from the state, and one even hung. A vigilante group in Dallas lynched three enslaved African Americans—Sam, Cato, and Patrick—who were suspects of starting a fire that burnt most of the downtown area. Other slaves in the county received whippings.

Then comes Juneteenth in 1865, immediately followed by what is called the Black Codes in 1865 and 1866. The Black Codes were a series of statutes and laws enacted in 1865 and 1866 by the legislatures of the Southern states of Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Virginia, Florida, Tennessee, and North Carolina following the end of the Civil War at the beginning of the Reconstruction Era. The Black Codes were created to restrict the freedom of ex-slaves in the South. Though most identify the Black Codes with the southern states previously mentioned, Texas too, implemented those same laws. Now, in theory, the entire southern region of African Americans are free with no money and no land. Some left the plantation to reunite with their family, some stayed and became sharecroppers, to mention a few instances. White Texans continued reacting to the end of the Civil War by increasing violence and attacks against African Americans. The Ku Klux Klan was ever present in Texas by 1868. Newly freed African Americans found themselves still restricted and targeted.

However, one of the many revolutionary acts of African Americans after Juneteenth came from what was considered the communities elite, the local musician. By this point, the music of African Americans that brought the community together on plantations had evolved into guitar traveling bluesman and songsters. As newly freed African Americans searched for families, worked to find a place in the new terrain of freedom, facing vicious attacks and aggressive blocks of rights, the musicians, as well as the preachers, brought a sense of comfort by sticking to the traditions we developed during the days of the plantations. They reached back to a time where they would be able to congregate peacefully in the woods away from Massa, whether to hear the word of God or hear the sounds of the local musicians while dancing and frolicking.

With the light benefits slave musicians were allotted due to working the white master’s social gatherings, what was more important was their unique status amongst our people on the plantations. In the African American Tribal Music article on Jack Dappa Blues, it states that the two most important roles in the African American community during plantation life and they were the roles of musicians and preachers, and after the end of slavery, our ancestors found themselves in a society of political corruption. This corruption rose up a group of newly freed African Americans who would assume roles as community advocates and congressman. At the same time, this modern version of oppression and disenfranchisement called for a traditional antidote.

During the days of slavery, masters would allow slaves to travel to nearby plantations for gatherings and the like. Like the Hot Supper, the gatherings were where blacks were able to enjoy themselves and each other away from white eyes and demands. Like it is twin the church, these gatherings were extremely sacred and a way to release the tension of white supremacy, usually held in the woods. From Texas throughout the South, African Americans after the emancipation would continue this tradition as a sense of recreating the community and kinship they once shared before this unfamiliar atmosphere. Many ex-slaves have stated that black folk would come from all over to attend these escapades.

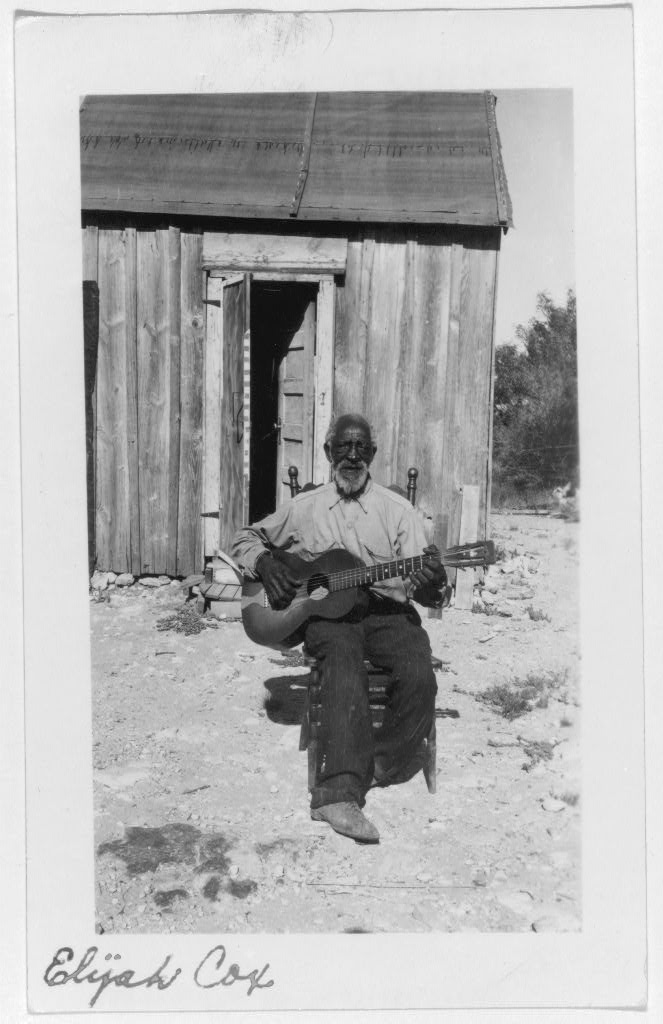

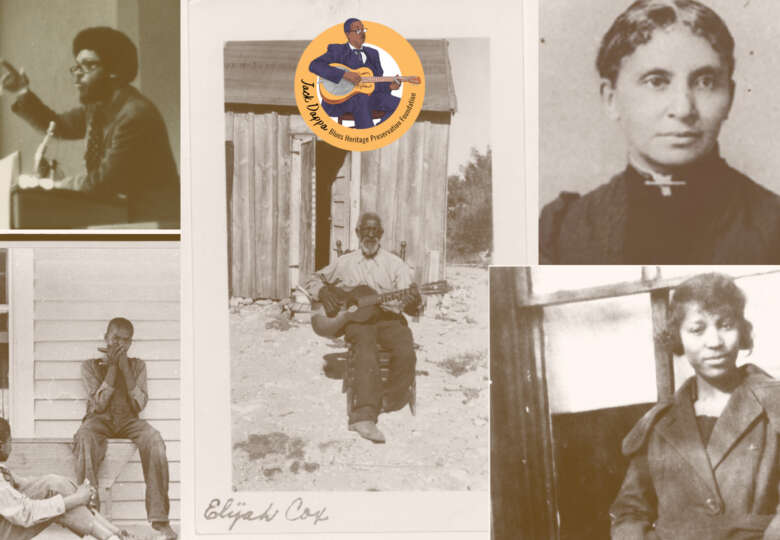

Musicians during the days of the plantation and slavery not only entertained, but they were folklorists and teachers. They were the griots and holders of the scrolls. They passed on Black Folklore and dances, and they taught songs of generations past, they connected the ancestors to the present and prepared the youngsters to carry it on for the future. This passing on of tradition through song and musicianship was to guarantee that our culture and heritage would remain and continued actively. Some were master entertainers, and others were practitioners who kept and passed on the stories and history. A great example of that is Texas Songster Elijah Cox, who sang a song called “Cruel Ol Slave Days” that he learned while he was stationed and living at Fort Concho, in San Angelo, Texas from an ex-slave. He eventually performed that song, and others for the Library of Congress in 1935 at the age of 93.

In Texas, many fiddlers blew the sox off of the audience. They were essential in this new climate. The cutting competitions that showed off the skills and tricks of musicians not only entertained but allowed for mental relaxation away from the current circumstances of the laws that prevented African Americans from living the life of a free human being. It also, yet again, reminded the folk of a close-knit community that was being destroyed by federal and state legislation.

The blues, the black spirituals, the singers and musicians, were the repository of folk culture and direct representatives of the peoples’ identity. This role remained during and well past the reconstruction era. However, what is not spoken about too often is the change in the direction of the lyrics that were being sung by these musicians and holders of traditional scrolls. With new free problems, and more space for frolicking, the content of song modernized to address the post-Juneteenth world of the African American.

Like days past, musicians were still able to travel. This traveling brought stories and names that represented regions, unlike before when the name represented their master musicianship. Many would say the Blues and other African American Traditional Music of the day were not political, nor did it address issues of the day, but that is false. African American Traditional music always represented social, economic, injustice, and spiritual issues. The difference now is, the lyrics became openly descriptive. Were as on the plantation in front of master, one would need to sing in codes for safety and such, now, off of the plantation, with freedom dangling in the face of our ancestors, and still facing deathly dangers, there was an opportunity to loosen the tongue and sing what was really going on.

Moreover, what was going on was lynching, distributing of barren land, legislation that called for the arrest of free blacks who were merely walking the streets, as well as, those who were free with nowhere to go yet, were arrested. Those arrests lead to prison farms. (We will deal with that in another article.) All of these issues, including the emergence of the communities tough guys began to materialize through the musical folklore of Blues, Ragtime, Songsters, Minstrels and the like.

Today, many celebrate and others are introduced to Juneteenth and its meaning. However, the Blues, Black Spirituals, and all African American Traditional Music should is a pivotal part that must continue to pass on when enjoying Juneteenth and the victory of the Texas slaves freedom. That is what the ancestors did, and that is what they wanted! That is the reason why so many early practitioners were folklorists and teachers to make sure we continued to represent and share our story. We must actively preserve the Narrative that was given by the elders.

References –

Juneteenth and Beyond: African American Emancipations …. http://www.hnn.us/article/172262

AFRICAN AMERICANS | The Handbook of Texas Online| Texas …. https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/pkaan

Black Codes: Restricting Freedom of ex-slaves. http://www.american-historama.org/1866-1881-reconstruction-era/black-codes.htm

Native-designed wool and cotton blankets by a Native-owned …. https://eighthgeneration.com/collections/blankets