Published By:

Lamont Jack Pearley

On this episode we will be looking into and discussing Eileen Southern, a scholar of Renaissance and African-American music and the first black woman to be appointed a tenured full professor at Harvard University, and her works.

After that, I have the honor to speak with Shirley Moody Turner, an associate professor of English and African American Studies. She is the author of Black Folklore and the Politics of Racial Representation, co-editor of Contemporary African American Literature: The Living Canon, and has recently signed on as editor of volume VII (focusing on the years 1900-1910) for the Cambridge University Press multi-volume project, African American Literature in Transition. Along with all her works, we will be discussing her latest project The Anna Julia Cooper Digital Project!

Black Folklore and the Politics of Racial Representation

An examination of how nineteenth- century African American folklore studies became a site of national debate

Before the innovative work of Zora Neale Hurston, folklorists from the Hampton Institute collected, studied, and wrote about African American folklore. Like Hurston, these folklorists worked within but also beyond the bounds of white mainstream institutions. They often called into question the meaning of the very folklore projects in which they were engaged.

Before the innovative work of Zora Neale Hurston, folklorists from the Hampton Institute collected, studied, and wrote about African American folklore. Like Hurston, these folklorists worked within but also beyond the bounds of white mainstream institutions. They often called into question the meaning of the very folklore projects in which they were engaged.

Shirley Moody-Turner analyzes this output, along with the contributions of a disparate group of African American authors and scholars. She explores how black authors and folklorists were active participants-rather than passive observers- in conversations about the politics of representing black folklore. Examining literary texts, folklore documents, cultural performances, legal discourse, and politi

cal rhetoric, Black Folklore and the Politics of Racial Representation demonstrates how folklore studies became a battleground across which issues of racial identity and difference were asserted and debated at the turn of the twentieth century. The study is framed by two questions of historical and continuing import. What role have representations of black folklore played in constructing racial identity? And, how have those ideas impacted the way African Americans think about and creatively engage black traditions?

Moody-Turner renders established historical facts in a new light and context, taking figures we thought we knew-such as Charles Chesnutt, Anna Julia Cooper, and Paul Laurence Dunbar- and recasting their place in African American intellectual and cultural history.

Shirley Moody-Turner, State College, Pennsylvania, is associate professor of English and African American studies at Pennsylvania State University. She is coeditor of Contemporary African American Literature: The Living Canon. She has also published essays on African American literature, race, and folklore in New Essays on the African American Novel, A Companion to African American Literature, and African American Review.

http://www.upress.state.ms.us/books/2063

Charles W. Chesnutt was born June 20, 1858, in Cleveland Ohio, the eldest child of Andrew Jackson Chesnutt and Anne Maria Sampson, free blacks from North Carolina. The increasing civil turmoil regarding slavery and coming political unrest forced Charles Chesnutt’s parents to move to Ohio, where they remained before the end of Civil War, and came back to Fayetteville, North Carolina with five young children. Charles’s father, Andrew Jackson Chesnutt, was a product of union between Waddell Cade, a prosperous slaveholding farmer and Ann Chesnutt, his mistress and later his housekeeper.

Charles’s mother also descended from a free mulatto Fayetteville family. Charles Chesnutt’s family heritage gave him the features that barely distinguished him from whites, but determined his social status as lower than that of the white Americans.

That Chesnutt’s works are centered around social issues, racism in particular, is not accidental and is mainly due to the environment and experiences in Chesnutt’s life. He was born two years before the Civil War, grew up in a turbulent sociopolitical atmosphere, and experienced the futile attempts of Reconstruction of Southern states.

After settling in Fayetteville at the age of eight, Charles started working at the grocery shop operated by his father, and attended the school set up by Freedman’s Bureau. After the death of his mother, Charles decided to contribute to the family’s poor budget by taking position at the school as pupil teacher. Deprived of the opportunity of formal education, Charles continued vigorous self education while teaching in various black educational institutions.

After teaching at black schools of Spartanburg, South Carolina, and Charlotte, North Carolina, Charles returned to Fayetteville in 1877 to become an assistant principal of the normal school. Here Charles met his colleague and future wife, Susan Perry, daughter of a prosperous barber. They got married in 1878. Being in a new position of a family man, Charles Chesnutt stood before two important decisions: determining the place for him and his family to settle and deciding on his future career. Despite his physical features that gave him close look to whites, Charles Chesnutt’s chances of success in impoverished and deeply prejudiced South were minimal. His mixed racial heritage was a burden that would always haunt him in the South. The entry in his personal journal shows Charles’s opinion about his place in the society of the South:

“I occupy here a position similar to that of Mahomet’s Coffin. I am neither fish, flesh, nor fowl-neither “nigger,” white, nor “buckrah.” Too “stuck-up” for the colored folks, and, of course, not recognized by the whites.”

Courtesy of the Chestnutt Archive.

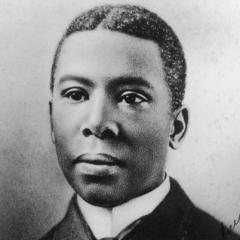

Paul Laurence Dunbar published in such mainstream journals as Century, Lipincott’s Monthly, the Atlantic Monthly, and the Saturday Evening Post. A gifted poet and a precursor to the Harlem  Renaissance, Dunbar was read by both blacks and whites in turn-of-the-century America.

Renaissance, Dunbar was read by both blacks and whites in turn-of-the-century America.

Dunbar, the son of two former slaves, was born in Dayton, Ohio, and attended the public schools of that city. He was taught to read by his mother, Matilda Murphy Dunbar, and he absorbed her homespun wisdom as well as the stories told to him by his father, Joshua Dunbar, who had escaped from enslavement in Kentucky and served in the Massachusetts 55th Regiment during the Civil War. Thus, while Paul Laurence Dunbar himself was never enslaved, he was one of the last of a generation to have ongoing contact with those who had been. Dunbar was steeped in the oral tradition during his formative years and he would go on to become a powerful interpreter of the African American folk experience in literature and song; he would also champion the cause of civil rights and higher education for African Americans in essays and poetry that were militant by the standards of his day.

During his years at Dayton’s Central High, Dunbar was the school’s only student of color, but it was his scholarly performance that distinguished him. He served as editor in chief of the school paper, president of the literary society, and class poet. His poetry grew more sophisticated with his repeated readings of John Keats, William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Robert Burns; later he would add American poets John Greenleaf Whittier, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and James Whitcomb Riley to his list of favorites as he searched ardently for his own poetic voice. But it was his reading of Irwin Russell and other writers in the plantation tradition that led him into difficulty as he searched for an authentic poetic diction that would incorporate the voices of his parents and the stories they told.

After graduating from high school in 1891, racial discrimination forced Dunbar to accept a job as an elevator operator in a Dayton hotel. He wrote on the job during slack hours. He became well known as the “elevator boy poet” after James Newton Mathews invited him to read his poetry at the annual meeting of the Western Association of Writers, held in Dayton in 1892.

In 1893 Dunbar published his first volume of poetry, Oak and Ivy, on the press of the Church of the Brethren. That same year he also attended the World’s Columbian Exposition, where he sold copies of his book and gained the patronage of Frederick Douglass and other influential African Americans.

Courtesy of American Modern Poetry

Anna Julia Haywood Cooper was a writer, teacher, and activist who championed education for African Americans and women. Born into bondage in 1858 in Raleigh, North Carolina, she was the daughter of an enslaved woman, Hannah Stanley, and her owner, George Washington Haywood.

Anna Julia Haywood Cooper was a writer, teacher, and activist who championed education for African Americans and women. Born into bondage in 1858 in Raleigh, North Carolina, she was the daughter of an enslaved woman, Hannah Stanley, and her owner, George Washington Haywood.

In 1867, two years after the end of the Civil War, Anna began her formal education at Saint Augustine’s Normal School and Collegiate Institute, a coeducational facility built for former slaves. There she received the equivalent of a high school education.

Anna Haywood married George A.G. Cooper, a teacher of theology at Saint Augustine’s, in 1877. When her husband died in 1879, Cooper decided to pursue a college degree. She attended Oberlin College in Ohio on a tuition scholarship, earning a BA in 1884 and a Masters in Mathematics in 1887. After graduation Cooper worked atWilberforce University and Saint Augustine’s before moving to Washington, D.C. to teach at Washington Colored High School. She met another teacher, Mary Church (Terrell), who, along with Cooper, boarded at the home of Alexander Crummell, a prominent clergyman, intellectual, and proponent of African American emigration toLiberia.

Cooper published her first book, A Voice from the South by a Black Woman of the South, in 1892. In addition to calling for equal education for women, A Voice from the South advanced Cooper’s assertion that educated African American women were necessary for uplifting the entire black race. The book of essays gained national attention, and Cooper began lecturing across the country on topics such as education, civil rights, and the status of black women. In 1902, Cooper began a controversial stint as principal of M Street High School (formerly Washington Colored High). The white Washington, D.C. school board disagreed with her educational approach for black students, which focused on college preparation, and she resigned in 1906.

Courtesy of BlackPast.org

An expert on the history of black music in America, Eileen Southern is credited with documenting and preserving musical traditions that had been all but ignored by the academic world. At a time  when many people though that jazz and blues was all there was to African-American music, Southern showed that, from the early 1600s, blacks in America created a richly diverse body of music ranging from spirituals and folks songs to choral works and symphonies.

when many people though that jazz and blues was all there was to African-American music, Southern showed that, from the early 1600s, blacks in America created a richly diverse body of music ranging from spirituals and folks songs to choral works and symphonies.

An acclaimed pianist as well as a scholar, Southern taught at several colleges and universities and in 1976 became the first black woman professor to receive tenure at Harvard University. Her landmark The Music of Black Americans: A History became the definitive text on the subject and established African-American music as a respected academic discipline. As Kay Shelemay, G. Gordon Watts Professor of Music, noted in a Harvard Gazette obituary, Southern was “an enormously distinguished scholar of Renaissance and African-American music and their history. She was a great lady and a great scholar who made important contributions to the field.”

Read more: Eileen Southern Biography – Grew Up with Music at Home, Created Black Music Curriculum, Overcame Challenges at Harvard, Selected writings – JRank Articles http://biography.jrank.org/pages/2989/Southern-Eileen.html#ixzz4xHe0x88c