Published By:

Lamont Jack Pearley

The Jan 1, 1863 Emancipation Proclamation of President Lincoln is a very important mark for the Blues People as it would forever change the dynamic of the African American experience and interactions in America, as well as the expressions that represented our daily life.

Though this particular entry is titled “the Emancipation”, we will also discuss The Reconstruction Period and Jim Crow because it is as a simultaneous combustion how these three events ruptured through the African American communities. To confirm this fact, let’s just look at the dates of these three events –

The Emancipation Proclamation – 1863

The Reconstruction Period – 1865 – 1877

Jim Crow – 1877

The Civil War between North and South was fought by the North to prevent the secession of the Southern states and preserve the Union. Even though sectional conflicts over slavery had been a major cause of the war, ending slavery was not a goal of the war. That changed on September 22, 1862, when President Lincoln issued his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which stated that slaves in those states or parts of states still in rebellion as of January 1, 1863, would be declared free.

With this Proclamation Lincoln hoped to inspire all blacks, and slaves in the Confederacy in particular, to support the Union cause and to keep England and France from giving political recognition and military aid to the Confederacy.

Because it was a military measure, however, the Emancipation Proclamation was limited in many ways. It applied only to states that had seceded from the Union, leaving slavery untouched in the loyal border states. It also expressly exempted parts of the Confederacy that had already come under Union control. Most important, the freedom it promised depended upon Union military victory.

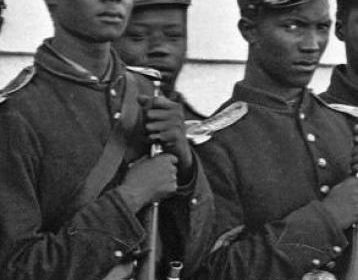

Although the Emancipation Proclamation did not end slavery in the nation, it did fundamentally transform the character of the war. After January 1, 1863, every advance of Federal troops expanded the domain of freedom. Moreover, the Proclamation announced the acceptance of black men into the Union Army and Navy, enabling the liberated to become liberators. By the end of the war, almost 200,000 black soldiers and sailors had fought for the Union and freedom.” (see:www.ourdocuments.gov)

Although the Emancipation Proclamation did not end slavery in the nation, it did fundamentally transform the character of the war. After January 1, 1863, every advance of Federal troops expanded the domain of freedom. Moreover, the Proclamation announced the acceptance of black men into the Union Army and Navy, enabling the liberated to become liberators. By the end of the war, almost 200,000 black soldiers and sailors had fought for the Union and freedom.” (see:www.ourdocuments.gov)

The period after the Civil War was called the Reconstruction period where Lincoln wanted to bring the Nation back together as quickly as possible which required that the States new constitutions prohibit slavery. In January 1865, Congress proposed an amendment to the Constitution which would abolish slavery in the United States. On December 18, 1865, Congress ratified the Thirteenth Amendment formally abolishing slavery. Abraham Lincoln was assassinated and Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s Vice President, briefly continued Lincoln’s policies. In May 1865, Johnson announced his own plans for Reconstruction which included a vow of loyalty to the Nation and the abolition of slavery that Southern states were required to take before they could be readmitted to the Nation. Black codes were adopted by midwestern states to regulate or inhibit the migration of free African-Americans to the midwest( The Great Migration). Cruel and severe black code laws were adopted by southern states after the Civil War to control or reimpose the old social structure. Southern legislatures passed laws that restricted the civil rights of the emancipated former slaves. This in fact can be considered the moment the Slave Secular becomes the Blues.

Freed African Americans now faced a world that was against them with no protection, in regards of ownership. This also altered the relationships between the African American. It can be looked at as the New Exodus, where internal struggles in regards to what and how things should be done began. It can and should also be looked at as how African Americans came together and built strong communities. An example of that is Uniontown, Alabama, where 4 million freed slaves roaming the antebellum, many of them who were ill prepared and unable to cope with the realities of their newfound freedom in 1865 rural Alabama, found the tenacity to develop their community, as well as institutions such as African American benevolent societies. Within the last couple of years, the most polarized society has been researched and it’s story produced into a documentary known as “The Contradiction Of Fair Hope” which is about the building, struggles, contributions and gradual loss of tradition of one of the last remaining African American benevolent societies,“The Fair Hope Benevolent Society”.

This is a huge breakthrough for a collective of people that now can work, praise, sing and socialize openly, while still living in the south.

With early success stories such as The Fair Hope Benevolent Society, there were still those who wanted to keep the old way of life. Mississippi was the first state to institute laws that abolished the full  civil rights of African-Americans. “An Act to Confer Civil Rights on Freedmen, and for Other Purposes,” a very misleading title, was passed in 1865. Other states quickly adopted their own versions of the codes, some of which were so restrictive that they resembled the old system of slavery such as forced labor for various offenses. (see: http://www.howard.edu)

civil rights of African-Americans. “An Act to Confer Civil Rights on Freedmen, and for Other Purposes,” a very misleading title, was passed in 1865. Other states quickly adopted their own versions of the codes, some of which were so restrictive that they resembled the old system of slavery such as forced labor for various offenses. (see: http://www.howard.edu)

Jim Crow Segregation was a way of life that combined a system of anti-black laws and race-prejudiced cultural practices. The term “Jim Crow” is often used as a synonym for racial segregation, particularly in the American South. The Jim Crow South was the era during which local and state laws enforced the legal segregation of white and black citizens from the 1870s into the 1960s. The term Jim Crow originated from the name of a black character from early- and mid- nineteenth century American theater. Crows are black birds, and Crow was the last name of a stock fictional black character, who was almost always played onstage by a white man in wearing blackface makeup. From the late 1800s, the name Jim Crow came to signify the social and legal segregation of black Americans from white.

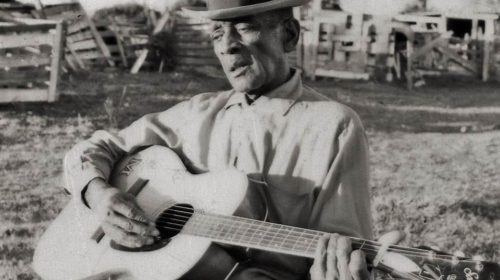

These major factors of the African American experience in America catapulted the evolution of black tribal music, where now instead of working the field in groups, African American’s were working alone, and if they were dealing in agriculture, they worked on land that was less desirable and fruitful, which was intentionally left for Negro purchase. The South was basically destroyed by the war, many people, families and homes were spread out. During this time, sticking to tradition, the workers who would sing in rows of slaves began to sing by themselves. And as they sang by themselves, they didn’t just sing for the helping hand of the Lord, but about missing their baby because she was so far away.

This also brings up the conversation of the Black Family. How it was affected, and how most scholars depicted their visions of the African American Family. According to Tristan L. Tolman, who wrote the article ‘The Effects of Slavery and Emancipation on African-American Families and Family History Research’, states “The condition of the black family in America has been an issue of intense debate since the Civil War. At the heart of this debate is the belief of some scholars that slavery created a propensity for a weak and fatherless family. This matrifocal (mother-centered) family, they argue, became typical of African Americans both during slavery and after emancipation and has been perpetuated generationally to the present time. Other scholars vehemently disagree. They counter that black American families cannot be classified as either weak or fatherless. These scholars maintain that blacks adapted to their difficult circumstances in creative ways to preserve familial ties.”

He goes on to say, “Although the end of the Civil War resulted in legal freedom for slaves, black families continued to face challenges in creating and preserving familial ties. It is important to define “family” as it has been used by African Americans.” This is where we get the community term, “Brotha”, “Sista” “Uncle” Auntie” or the neighborhood elder being referred to as “Ma”, or Mamma, as well as “Pop’ etc.

These kin networks formed the social basis of African-American communities.1 Slaves were often forcefully removed from their families. They adapted to their circumstances by creating family units with other slaves with whom they lived and worked. Slaves conferred the status of kin on non-blood relations, addressing each other as brother, sister, aunt, or uncle.2 Slave parents taught their children to address all older slave men and women by kin titles, a practice that bound them to these adults and prepared them in the event that sale or death separated them from their own parents and blood relatives.3 Parents relied on these kin networks to help them raise their children and understood that at any time, they may also need to assume the role of “aunt” or “uncle.”4 A black freedwoman remembered her uncle asking, “Should each man regard only his own children, and forget all the others?”5

The importance of this, besides the fact that the custom of kin folk has been carried on until today, is men frequently travelled long distances for work, leaving the family home who utilized the kin folk structure to survive. This is also found in fictional narratives by African American writers such as Mildred D Taylor in her book Role of Thunder, Hear My Cry, Furthermore, when men had to travel from town to town to find work, riding, working and hiding on the trains were one of the things that lead to sounds such as the 12 bar Blues shuffle, whether on guitar or harmonica.

During this time the popularity of juke houses and juke joints that were found on plantations grew. Bluesman and women would travel alone, and sometimes with a caravan of entertainers to perform throughout and around the plantations entertaining the folk who lived and worked there. This practice went on throughout the entire south and other regions as well. The most popular form of this traveling show was known as Vaudeville, which later became the foundation of black face minstrel shows. It also birthed what became known as “Classic Blues” where the woman Blues singer headlined the show, as well as ran the business of the show.

During this time the popularity of juke houses and juke joints that were found on plantations grew. Bluesman and women would travel alone, and sometimes with a caravan of entertainers to perform throughout and around the plantations entertaining the folk who lived and worked there. This practice went on throughout the entire south and other regions as well. The most popular form of this traveling show was known as Vaudeville, which later became the foundation of black face minstrel shows. It also birthed what became known as “Classic Blues” where the woman Blues singer headlined the show, as well as ran the business of the show.

Free Blacks also meant an over crowded employment population. It meant that white owners had to pay former captives for their labor. It meant a heavy competition in the job market that was thought to be for only white families. It meant lynchings. It meant false arrests that lead to many years to life on prison farms. It meant traveling through Mississippi, Alabama, Texas, Georgia, Louisiana, South Carolina and so on, not knowing whether one would see another day free let alone alive. Which is a direct reflection of the days of slavery that actually created the “Kin Folk” community.

This danger was as minuscule as walking along the street.

“An invisible hand ruled their lives and the lives of all the colored people in Chickasaw County and the rest of Mississippi and the entire South for that matter. It wasn’t one thing; it was everything. The hand had determined that white people were in charge and colored people were under them and had to obey them…” p31 The Warmth of the Other Sun

Mississippi, like the rest of the South had unspoken rules that were to be adhered to. African Americans had to step off of the curb when a white person was passing by them, even a welcoming hello to a white woman ended in death whether by judicial sentencing or angry mob. School for Black children met when they didn’t have to work the fields.

South Carolina, what could be considered one of the most violent states in America dating back to November 1784 and the Cloud’s Creek Massacre, a place where Benjamin Franklin chastised them for being “White Savages”, not only was a leader in and strong advocate for the Civil War, but they were also amongst the spearheading states that perpetuated the intimidating, killing and defrauding of African Americans that ended reconstruction in South Carolina. And these moments in history forced African Americans into another form of survival, that were reflected in song.

[shopify embed_type=”product” shop=”godsfamily1st.myshopify.com” product_handle=”blues-music-is-black-history-3″ show=”all”]

Louisiana, where creole and mulattos received special treatment because of their fair skin, learned a harsh lesson during Jim Crow. In 1891, the Louisiana legislature had officially segregated the railroads within the state. In 1892, Homer Plessy, an active member of a New Orleans civil rights organization, the Comité de Citoyens, bought a first-class ticket on a train and attempted to sit among whites. After he was arrested for breaking the law, Plessy sued the railroad company, his lawyers arguing that segregation denied him equal protection under the law as guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. In 1896, however, the US Supreme Court upheld Louisiana law in its decision on Plessy vs. Ferguson. Speaking for the majority, Justice Henry Brown stated that segregation did not deprive Plessy of his rights, nor did it make him an inferior person. The justices argued that states could establish “separate but equal” facilities; if blacks and whites were treated equally, segregation would be allowed to stand. Yet, in almost all public facilities—schools, hospitals, trains, restaurants, hotels, parks, cemeteries, the armed forces, and jury duty—whites received priority over African Americans. Following the decision, some institutions excluded African Americans altogether. Two years after the Plessy decision, Louisiana passed one of the first laws officially stripping blacks of the right to register to vote. In essence, everything that could be segregated in Louisiana was. Public facilities for adults, including restaurants, hotels, night clubs, and cemeteries, were strictly segregated, as were public facilities for children such as amusement parks, playgrounds, and schools. By 1900, the line separating whites and blacks had become deeply entrenched in Louisiana’s culture. (see: Know Louisiana) That categorized all blacks, whether mullato, creole or one-eighth or more negro just as Black as their darker skinned counterparts on the other side of the tracks forcing the internationally educated fair skinned musicians to have to “slum” with the colored folk and play Blues. This was ONE of the catalysts of Jazz. Piano Blues, Jump Blues mixed with brass instruments that made it’s way to and was popular in New York City.

“Throughout Africa storytellers hold an esteemed place in the community. They are the repositories of knowledge. They are the teachers. They pass down their wisdom through stories, the symbolic  imagery of their experience. This oral tradition has been passed along and is evident in African American culture today.” (p37 Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome – Dr Joy DeGruy)

imagery of their experience. This oral tradition has been passed along and is evident in African American culture today.” (p37 Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome – Dr Joy DeGruy)

Facing such turbulence, a new church and minister evolved. Their message wasn’t only one based on promised lands or afterlife, but it was dealing with the here and now. They were the new repositories of tradition, culture and heritage. The New Priests of the black community, the New Orator was the bluesmen and women, and their songs were the blues. Knowing that the tradition of the Negro stems from the passing down of history and heritage through word of mouth, as well as expressing current circumstances, who better.

The Blues are the essential ingredients that define the essence of the black experience. The Blues tell us about the strength of black people to survive, and to shape existence while living in the midst of oppressive contradictions. They also tell us about the joy and sweetness of love. (p106 James H Cone The Spirituals and The Blues)

Blues means Negro experience, it is the one music the Negro made that could not be transferred into a more general significance than the one the Negro gave it initially – (p94 LeRio Jones Blues People)

SEE NEXT ARTICLE – THE GREAT MIGRATION

1 Herbert G. Gutman, The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom, 1750–1925 (New York: Pantheon Books, 1976), 3. 2 Ira Berlin and Leslie S. Rowland, Families and Freedom: A Documentary History of African-American Kinship in the Civil War Era (New York: New Press, 1997), 3. 3 Gutman, The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom, 219. 4 Berlin and Rowland, Families and Freedom, 8. 5 Laura M. Towne, as quoted in Gutman, The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom, 185