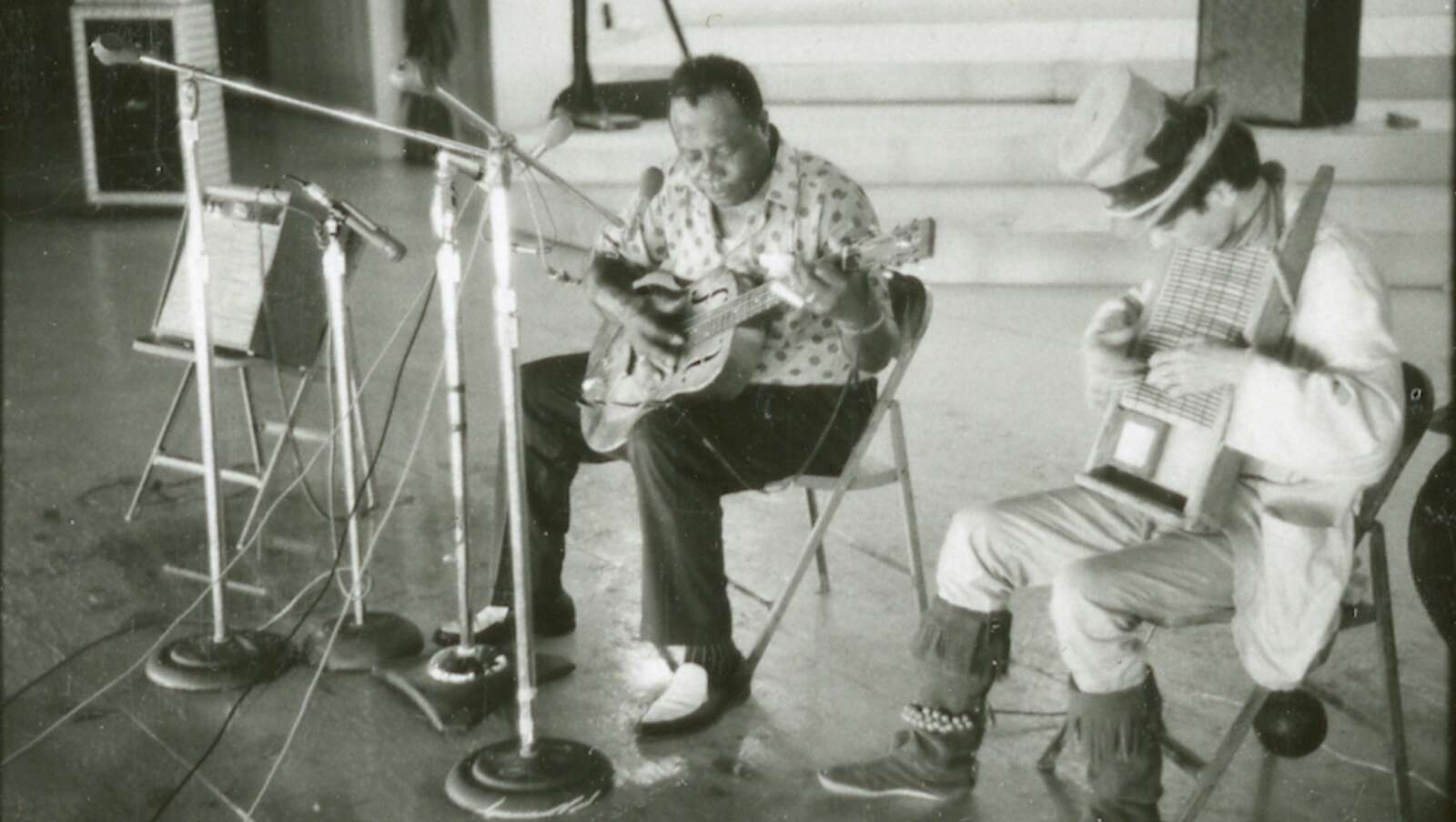

By: Lamont Jack Pearley January 31, 1865—a date that marked a turning point in American history with the passing of the 13th Amendment, abolishing slavery. But true freedom extended far beyond legal documents; it was carried in the voices, rhythms, and cultural…