Published by

Lamont Jack Pearley

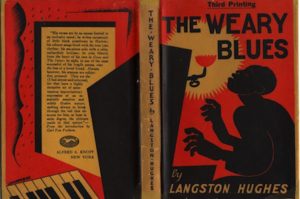

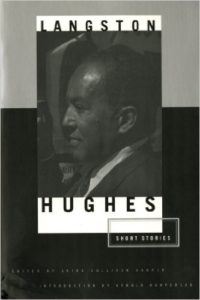

African American History, The Blues, African American Literature and our culture is and has always been one in the same. And in celebrations to that, I wish to post an excerpt of a great short story by the amazing Langston Hughes called — “The Blues I’m a Playin’”

Enjoy the read–

Works by Langston Hughes

Oceola Jones, pianist, studied under Philippe in Paris. Mrs. Dora Ellsworth paid her bills. The bills included a little apartment on the Left Bank and a grand piano. Twice a year Mrs. Ellsworth came over from New York and spent part of her time with Oceola in the little apartment. The rest of her time abroad she spent at Biarritz or Juan les Pins, where she would see the new canvases of Antonio Bas, young Spanish painter who also enjoyed the patronage of Mrs. Ellsworth. Bas and Oceola, the woman thought, both had genius. And whether they had genius or not, she loved them, and took good care of them.

Oceola Jones, pianist, studied under Philippe in Paris. Mrs. Dora Ellsworth paid her bills. The bills included a little apartment on the Left Bank and a grand piano. Twice a year Mrs. Ellsworth came over from New York and spent part of her time with Oceola in the little apartment. The rest of her time abroad she spent at Biarritz or Juan les Pins, where she would see the new canvases of Antonio Bas, young Spanish painter who also enjoyed the patronage of Mrs. Ellsworth. Bas and Oceola, the woman thought, both had genius. And whether they had genius or not, she loved them, and took good care of them.

Poor dear lady, she had no children of her own. Her husband was dead. And she had no interest in life now save art, and the young people who created art. She was very rich, and it gave her pleasure to share her richness with beauty. Except that she was sometimes confused as to where beauty lay — in the youngsters or in what they made, in the creators or the creation. Mrs. Ellsworth had been known to help charming young people who wrote terrible poems, blue-eyed young men who painted awful pictures. And she once turned down a garlic-smelling soprano-singing girl who, a few years later, had all the critics in New York at her feet. The girl was so sallow. And she really needed a bath, or at least a mouth wash, on the day when Mrs. Ellsworth went to hear her sing at an East Side settlement house. Mrs. Ellsworth had sent a small check and let it go at that — since, however, living to regret bitterly her lack of musical acumen in the face of garlic.

About Oceola, though, there had been no doubt. The Negro girl had been highly recommended to her by Ormond Hunter, the music critic, who often went to Harlem to hear the church concerts there, and had thus listened twice to Oceola’s playing.

“A most amazing tone,” he had told Mrs. Ellsworth, knowing her interest in the young and unusual. “A flare for the piano such as I have seldom encountered. All she needs is training — finish, polish, a repertoire.”

“Where is she?” asked Mrs. Ellsworth at once. “I will hear her play.”

By the hardest, Oceola was found. By the hardest, an appointment was made for her to

come to East 63rd Street and play for Mrs. Ellsworth. Oceola had said she was busy every day. It seemed that she had pupils, rehearsed a church choir, and played almost nightly for colored house parties or  dances. She made quite a good deal of money. She wasn’t tremendously interested, it seemed, in going way downtown to play for some elderly lady she had never heard of, even if the request did come from the white critic, Ormond Hunter, via the pastor of the church whose choir she rehearsed, and to which Mr. Hunter’s maid belonged.

dances. She made quite a good deal of money. She wasn’t tremendously interested, it seemed, in going way downtown to play for some elderly lady she had never heard of, even if the request did come from the white critic, Ormond Hunter, via the pastor of the church whose choir she rehearsed, and to which Mr. Hunter’s maid belonged.

It was finally arranged, however. And one afternoon, promptly on time, black Miss Oceola Jones rang the door bell of white Mrs. Dora Ellsworth’s grey stone house just off Madison. A butler who actually wore brass buttons opened the door, and she was shown upstairs to the music room. (The butler had been warned of her coming.) Ormond Hunter was already there, and they shook hands. In a moment, Mrs. Ellsworth came in, a tall stately grey-haired lady in black with a scarf that sort of floated behind her. She was tremendously intrigued at meeting Oceola, never having had before amongst all her artists a black one. And she was greatly impressed that Ormond Hunter should have recommended the girl. She began right away, treating her as a protegee; that is, she began asking her a great many questions she would not dare ask anyone else at a first meeting, except a protegee. She asked her how old she was and where her mother and father were and how she made her living and whose music she liked best to play and was she married and would she take one lump or two in her tea, with lemon or cream?

After tea, Oceola played. She played the Rachmaninoff Prelude in C Sharp Minor. She played from the Liszt Etudes. She played the St. Louis Blues. She played Ravel’s Pavannne pour une Enfante Défunte.And then she said she had to go. She was playing that night for a dance in Brooklyn for the benefit of the Urban League.

Mrs. Ellsworth and Ormond Hunter breathed, “How lovely!”

Mrs. Ellsworth said, “I am quite overcome, my dear. You play so beautifully.” She went on further to say, “You must let me help you. Who is your teacher?”

“I have none now,” Oceola replied. “I teach pupils myself. Don’t have any more time to study — nor money either.”

“But you must have time,” said Mrs. Ellsworth, “and money, also. Come back to see me on Tuesday. We will arrange it, my dear.”

And when the girl had gone, she turned to Ormond Hunter for advice on piano teachers to instruct those who already had genius, and need only to be developed.

Then began one of the most interesting periods in Mrs. Ellsworth’s whole experience in

aiding the arts. The period of Oceola. For the Negro girl, as time went on, began to occupy a greater and greater place in Mrs. Ellsworth’s interests, to take up more and more of her time, and to use up more and more of her money. Not that Oceola ever asked for money, but Mrs. Ellsworth herself seemed to keep thinking of so much more Oceola needed.

At first it was hard to get Oceola to need anything. Mrs. Ellsworth had the feeling that the girl mistrusted her generosity, and Oceola did — for she had never met anybody interested in pure art before. Just to be given things for art’s sake seemed suspicious to Oceola. That first Tuesday, when the colored girl came back at Mrs. Ellsworth’s request, she answered the white woman’s questions with a why-look in her eyes.

“Don’t think I’m being personal, dear,” said Mrs. Ellsworth, “but I must know your background in order to help you. Now, tell me . . .”

Oceola wondered why on earth the woman wanted to help her. However, since Mrs. Ellsworth seemed interested in her life’s history, she brought it forth so as not to hinder the progress of the afternoon, for she wanted to get back to Harlem by six o’clock.

Born in Mobile in 1903. Yes, ma’am, she was older than she looked. Papa had a band, that is her step-father. Used to play for all the lodge turn-outs, picnics, dances, barbecues. You could get the best roast pig in the world in Mobile. Her mother used to play the organ in church, and when the deacons bought a piano after the big revival, her mama played that, too. Oceola played by ear for a long while until her mother taught her notes. Oceola played an organ, also, and a cornet.

Born in Mobile in 1903. Yes, ma’am, she was older than she looked. Papa had a band, that is her step-father. Used to play for all the lodge turn-outs, picnics, dances, barbecues. You could get the best roast pig in the world in Mobile. Her mother used to play the organ in church, and when the deacons bought a piano after the big revival, her mama played that, too. Oceola played by ear for a long while until her mother taught her notes. Oceola played an organ, also, and a cornet.

“My, my,” said Mrs. Ellsworth.

“Yes, ma’am,” said Oceola. She had played and practiced on lots of instruments in the South before her step-father died. She always went to band rehearsals with him.

“And where was your father, dear?” asked Mrs. Ellsworth.

“My step-father had the band,” replied Oceola. Her mother left off playing in the

church to go with him traveling in Billy Kersands’ Minstrels. He had the biggest mouth in the world, Kersands did, and used to let Oceola put both her hands in it at a time and stretch it. Well, she and her mama and step-papa settled down in Houston. Sometimes her parents had jobs and sometimes they didn’t. Often they were hungry, but Oceola went to school and had a regular piano-teacher, an old German woman, who gave her what technique she had today.

“A fine old teacher,” said Oceola. “She used to teach me half the time for nothing. God bless her.”

“Yes,” said Mrs. Ellsworth. “She gave you an excellent foundation.”

“Sure did. But my step-papa died, got cut, and after that Mama didn’t have no more use for Houston so we moved to St. Louis. Mama got a job playing for the movies in a Market Street theater, and I played for a church choir, and saved some money and went to Wilberforce. Studied piano there, too. Played for all the college dances. Graduated. Came to New York and heard Rachmaninoff and was crazy about him. Then Mama died, so I’m keeping the little flat myself. One room is rented out.”

“Is she nice?” asked Mrs. Ellsworth, “your roomer?”

to finish the story…either buy Langston Hughes “Short Stories” or click to Read more here