Published By

Lamont Jack Pearley

In our quest to cultivate the African-American, Black American, Negro, Nubian etc, community to not only accumulate a wealthy Library of African American Literature, but to actually read and study our history, heritage and continued climate in the world, I’ve come across a book that I would like to suggest everyone reads. Now, I haven’t read it yet, but it’s one of my next purchases. I’ve decided to stop buying books until I finish the books that I’ve recently purchased. And I’ve purchased many in the recent months…meaning I’m a little backed up.

However, in researching an article I’m currently working on, I came across a book that,

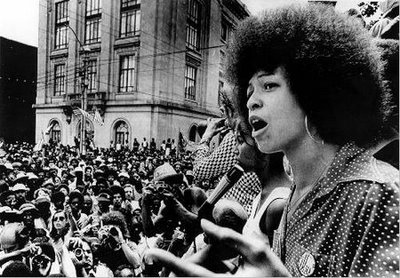

in reading the synopsis, I think it’s worthy of not only a read, but a purchase for your home library. Not to mention it’s written by a pillar of our community, activism and fight for true justice, liberation and social and economic freedoms. Angela Y Davis. The books title is Blues Legacies and Black Feminism: Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday —

Here’s an excerpt of Chapter one –

By ANGELA Y. DAVISPantheon Books

Ideology, Sexuality, and Domesticity

You’ve had your chance and proved unfaithful

So now I’m gonna be real mean and hateful

I used to be your sweet mama, sweet papa

But now I’m just as sour as can be.

–“I Used to Be Your Sweet Mama,”

Like most forms of popular music, African-American blues lyrics talk about love. What is distinctive about the blues, however, particularly in relation to other American popular musical forms of the 1920s and 1930s is their intellectual independence and representational freedom. One of the most obvious ways in which blues lyrics deviated from that era’s established popular musical culture was their provocative and pervasive sexual–including homosexual–imagery.

By contrast, the popular song formulas of the period demanded saccharine and idealized nonsexual depictions of heterosexual love relationships. Those aspects of lived love relationships that were not compatible with the dominant, etherealized ideology of love–such as extramarital relationships, domestic violence, and the ephemerality of many sexual partnerships–were largely banished from the established popular musical culture. Yet these very themes pervade the blues. What is even more striking is the fact that initially the professional performers of this music–the most widely heard individual purveyors of the blues–were women. Bessie Smith earned the title “Empress of the Blues” not least through the sale of three-quarters of a million copies of her first record.

The historical context within which the blues developed a tradition of openly addressing both female and male sexuality reveals an ideological framework that was

specifically African-American. Emerging during the decades following the abolition of slavery, the blues gave musical expression to the new social and sexual realities encountered by African Americans as free women and men. The former slaves’ economic status had not undergone a radical transformation–they were no less impoverished than they had been during slavery. It was the status of their personal relationships that was revolutionalized. For the first time in the history of the African presence in North America, masses of black women and men were in a position to make autonomous decisions regarding the sexual partnerships into which they entered. Sexuality thus was one of the most tangible domains in which emancipation was acted upon and through which its meanings were expressed. Sovereignty in sexual matters marked an important divide between life during slavery and life after emancipation.

Themes of individual sexual love rarely appear in the musical forms produced during slavery. Whatever the reasons for this–and it may have been due to the slave system’s economic management of procreation, which did not tolerate and often severely punished the public exhibition of self-initiated sexual relationships–I am interested here in the disparity between the individualistic, “private” nature of sexuality and the collective forms and nature of the music that was produced and performed during slavery. Sexuality after emancipation could not be adequately expressed or addressed through the musical forms existing under slavery. The spirituals and the work songs confirm that the individual concerns of black people expressed through music during slavery centered on a collective desire for an end to the system that enslaved them. This does not mean there was an absence of sexual meanings in the music produced by African-American slaves. It means that slave music–both religious and secular–was quintessentially collective music. It was collectively performed and it gave expression to the community’s yearning for freedom.

Check it out!